The Basis

In Linear Algebra, we’re used to build a vector out of other vectors .

Each vector is, at the very least, implicitly constructed out of its basis vectors. If there is no specific basis mentioned anywhere, we assume it to be a basis of unit vectors. For instance, for a two-dimensional space these are and , and that a vector is just the sum of scaled basis vectors.

The numbers and are the coefficients of the basis vectors . We can call them .

The same is true for functions. We can build a function out of other functions and .

We can likewise represent one function as the sum of a set of scaled basis functions, just like we can represent one vector as a sum of scaled basis vectors.

The only question is, how do we know the scaling coefficients (i.e., and ) to build the desired function with a set of basis functions?

Function Transforms

When transforming a vector from one basis to another, what we do is to multiply the vector by each basis vector to get the new coefficients. The multiplication operation that we do is the dot product, or more generally the inner product , a kind of matrix multiplication to project onto each basis vector .

This can also be written as a product of the individual vector components and .

To reconstruct vector in the new basis, we simply multiply the basis by the coefficients.

Notice how Equation is just the general form of Equation . Transforming a function into a set of coefficients for a function basis is almost the same process as in Equation . Here we have to integrate it over the function domain with each basis function individually.

Note that the only difference between Equation and is that in one case we sum up a discrete representation (i.e., the vector components) and in the other we have to integrate it instead. This is why we write down an inner product rather than a dot product, because it is independent of the fact that the basis is one of functions, or vectors or anything else.

Reconstructing the original function works just as in Equation .

Function Basis Properties

With vectors, we can use the inner product (that is, a dot product) to determine some properties about their relationship. For instance, we can tell from the projection whether or not vectors and are orthonormal to one another.

If the coefficient is , then both vectors and are orthogonal to each other. Additionally if and happen to be identical and turns out to be and not an arbitrary number , then we know that both vectors also form an orthonormal basis. is called Kronecker Delta and is usually just a shorthand of such a basis behavior. With functions, the same concept is true, and the formula is identical. Instead of a dot product, the inner product for two functions and represents an integration. But again, if turns out to be , we know both functions are orthogonal to each other, and if every other result is , then the function basis is orthonormal.

We now have all the tools necessary to define properties of a function space: Equation can be used to define orthogonality and orthonormality of two functions, and can be used to define linear dependency (one function is a sum of scalar multiples of other functions of the same basis) and therefore also the rank and determinant of a function basis.

The Convolution Theorem

Now that we know how to transform a function into coefficients of a function basis, and how to test whether or not a function basis has certain properties like orthonormality, let’s perform a magic trick. Imagine we have an orthonormal basis , i.e. two functions of that basis will always integrate to if they are identical, or if they are not.

We can represent any function by a bunch of coefficients in that basis. Imagine now that we have two functions: and .

Let’s multiply them together and integrate the result. We can replace the functions with the sum in Equation and .

In Equation we can reorder some things because everything is linear: We can move the two sums and out of the integral, together with their coefficients, because they do not depend on .

However, we just noticed in the previous section that a function basis can be orthonormal. An orthonormal function basis is very nice to have, because the integrated product of the function basis vectors (i.e., the inner product of two functions) will be either or , so the integral in Equation can be replaced with the Kronecker Delta from Equation !

But if we have a Kronecker Delta, that just means that every time and are not equal, the product is just . So we can simplify even further and remove one variable.

What is this? Equation looks like a dot product. So in essence that means we can shortcut an integration of a product of two functions and by a dot product of their coefficients and if the function basis is orthonormal!

Why is this important?

Filtering

Filter operations always take on a formula just like Equation . For instance, a Gauss Filter is a Gauss function that is, in a small window, multiplied with another function. One can do that in a pixel-based domain, where each pixel is multiplied with a value from the Gauss function at the same position, but it is really just two functions multiplied together.

However, if one part of the function is already available in a harmonic basis function, for instance as a JPEG image, then we can apply the filter in the function basis directly and do an operation which would normally be very expensive with a cheap dot product! If the number of coefficients is smaller than the operations necessary on the original domain of the function (that is, the number of pixels we need to sum up), we can save a tremendous amount of computation time.

Precomputed Radiance Transfer

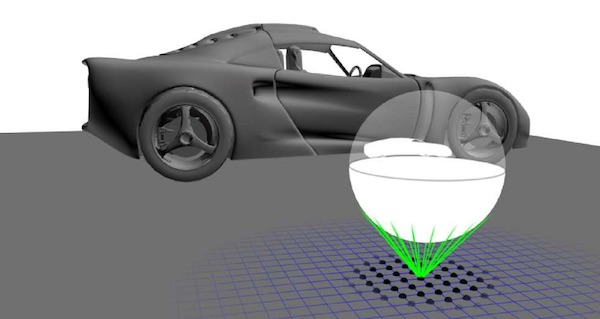

Transfer function visualized. Every white pixel in this image is one which, evaluated by a raytracer, was blocked by some geometry. All other pixels represent values where a ray shot from this point could travel freely away from all geometry.

Transfer function visualized. Every white pixel in this image is one which, evaluated by a raytracer, was blocked by some geometry. All other pixels represent values where a ray shot from this point could travel freely away from all geometry.

A main observation of Precomputed Radiance Transfer is the following: One can simplify the rendering equation to something we have seen above by throwing out self-emittance, and unify everything in the integral that isn’t incoming light into one homogeneous diffuse transfer function .

The transfer function is simply everything - materials, visibility, Lambert factor etc. - packed into a single function. A simple visualization is in the above figure, where the transfer function of a point shows a visibility function. Imagine now that next to a transfer function, we also have a function representing our environment light. The crucial observation is that Equation looks just like Equation , and this means that if we can get both as coefficients of some basis function, we can compute the integral in Equation with just one simple dot product of their coefficients!

Why is this practical? Getting the coefficients is really expensive, so before we can do this we would need to compute all transfer functions (probably with a raytracer) which is already very costly, and then do the Monte Carlo estimation to get their coefficients. This is way too expensive to do in real-time. But, if the car in the figure never moves, then the transfer function never changes! So if we compute all transfer in an offline step and save it (one might almost be tempted to call this pre-computing the transfer), then we only need to get the coefficients for the light at runtime, and that should be fairly easy to do. In fact, if we only have a bunch of different lighting configurations, we can precompute the coefficient vectors for all of them, and at runtime when switching between skyboxes fetch the respective coefficients.